The Hagakure #64: The Heart of W. Edwards Deming

“A leader is best when people barely know he exists, when his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say: we did it ourselves.” —Lao Tzu

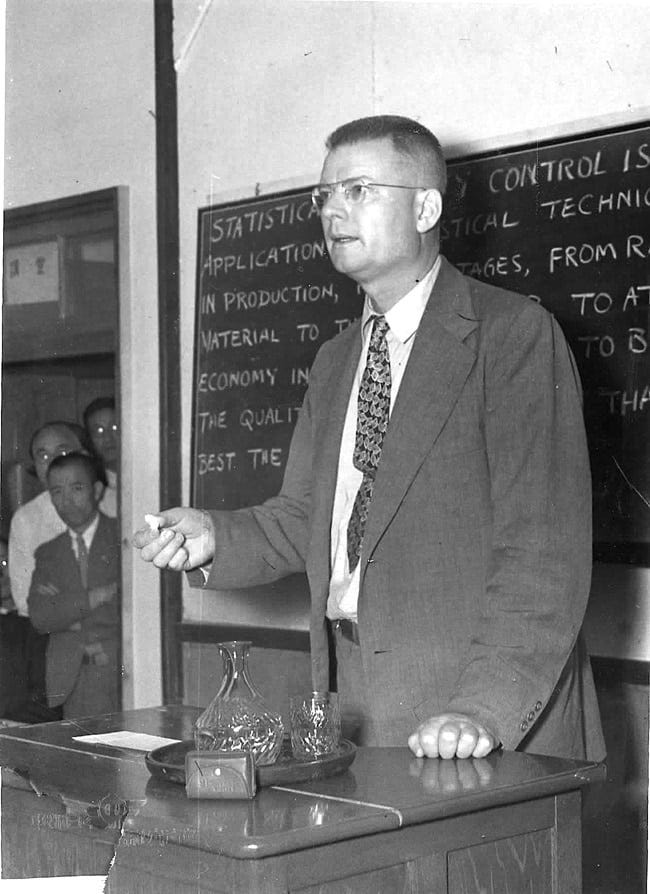

Most people never heard of W. Edwards Deming.

It’s a shame because his wisdom holds the keys to leading people and managing systems in a way that puts people and profit front and center.

He also made gigantic contributions not only to winning a World War (wish there never was such a need…) and then to rebuild one of the defeated countries—to the point of obliterating the victor’s automotive industry shortly thereafter.

He’s also the only American to have his picture framed next to the founders of Toyota in their headquarters in Japan, a company on which he had a profound impact in multiple ways. One in particular stands out: a deep belief that most problems are system problems that are the responsibility of management.

All of the above rested on the shoulders of Deming’s command of systems thinking and specifically of statistical process control. I thought that was a mouthful until I understood what it’s really about—statistically predicting defects before they occur.

In other words, you not only check quality but you systematically, and relentlessly improve the whole process leading to the output. And that’s how the United States won WW2—by outproducing everyone in both quantity and quality, creating an overwhelming advantage.

But as I’m reading John Willis’s excellent new book Deming’s Journey to Profound Knowledge, it’s not his thinking and brains that most inspire me.

It’s his heart.

Right after the war, Japan was a decimated country on its last legs. As an example, people were not allowed to sleep inside train stations not because of the cold—but because they were dying of hunger.

Destiny took Deming to Japan shortly after the war ended. He believed statistical process control held the keys to rebuilding the country. The US administration, however, wasn’t keen on that. They wanted the Japanese to suffer, to pay for what they did—two atomic bombs dropped on their heads and a sum total of ~3 million dead were not enough, it seems. But allied supreme commander General Douglas McArthur knew better, and created the conditions for the rebuilding.

Upon arrival, Deming (aka Ed) was confronted with a painful reality. Willis writes:

“The Professor was more than moved: he was moved to action. He began purchasing food from the military PX (post exchange) and carrying it around with him to pass out to the starving and destitute. When he toured an asylum, he found the patients neglected, malnourished, and abused. Ed did everything in his power to have the superintendent fired and replaced. When he crossed a canal to find a father with a little boy and girl in rags begging, he hurried back to the green zone to purchase a dozen doughnuts for them that very night.”

Astonishingly, he never took compensation for any his work:

“He readily accepted. In his reply, Ed wrote, ‘As for remuneration, I shall not desire any. It will be only a great pleasure to assist you.’ Later, he would again refuse any compensation, directing Koyanagi to use the collected lecture fees for the benefit of JUSE. When Moriguti published the translated version of Ed’s book, the Professor refused any royalties, again directing them to be used for the benefit of the Japanese. He was well aware of the hardships the unemployed and the unemployable statisticians faced.”

Deming would note later on that, to his knowledge, “he was the only man as part of an occupied force who’d ever been voluntarily invited to return to the conquered country by the conquered.”

Let that sink in.

So it happened that in 1950, during his second time in Japan, he spoke to twenty-one of the most influential executives at the time in the country. It was less a lecture than an impassioned plea. He believed Japan could rebuild, which according to Deming himself, “I was, in 1950, the only man in Japan who believed that.”

What happened next was stunning.

“Ed must have seemed like a madman to tell them that not only could they once again become a powerful nation, but that they could be back on their feet in just five years.

His prophecy was wrong: they did it in four.

By year five, the country had an enviable economic growth rate of 9%–10% per year. By the 1960s, Japan’s growth rate climbed even higher during the fabled Japanese economic miracle. By 1968, the country was the second-largest economy in the world—bigger than the UK, Italy, France, and the USSR. It would hold this distinction until 2010, when China edged it out.

Years later, Ed would come to be called “the Prophet.” He had seen what no one else could see. This was perhaps one of his greatest contributions to the people of Occupied Japan: he inspired hope, if not confidence.”

Why do I bring this up? Who cares about an old white man, who passed away in 1993, right?

Many reasons.

A big one is encapsulated in this beautiful passage from David Halberstam’s tale of the demise of the US automotive industry at the hands of the Japanese later on (emphasis mine):

“Arriving at a difficult time for the Japanese, Deming never condescended to them. He looked at them, and, unlike so many of his fellow citizens, he saw not their poverty but their purpose. At a moment when Americans were powerful and rich and the Japanese weak and vulnerable, he, unlike many Americans, never made them feel inferior. On the contrary, he genuinely reassured them. If this brilliant American expert believed in them, they could begin to believe in themselves.”

If we focus on never making others feel inferior, there’s no limit to what can be achieved, collectively, without burning ourselves and each other out in the process.

Deming was a master of systems thinking and understood complexity like few others. But what I learned from reading about his life, thanks to John Willis, is that none of that takes hold if your heart is not in the right place. He was a leader of people (often reluctantly so), and a supreme manager of systems.

…

Towards the end of the book, I’m reminded of one of my favorite books ever: Peter Senge’s The Fifth Discipline. Senge was relatively unknown then, but he asked Deming (then 90 years young) for feedback on the book. Perhaps surprisingly to him, Deming promptly returned his letter with a note Senge felt obliged to quote in the book’s introduction (emphasis again mine):

Our prevailing system of management has destroyed our people. People are born with intrinsic motivation, self-respect, dignity, curiosity to learn, joy in learning. The forces of destruction begin with toddlers—a prize for the best Halloween costume, grades in school, gold stars—and on up through the university. On the job, people, teams, and divisions are ranked, reward for the top, punishment for the bottom. Management by objectives, quotas, incentive pay, business plans, put together separately, division by division, cause further loss, unknown and unknowable.

So, over to you and me:

How can we lead with more heart and not only with the brain?

How can we stop mistaking care, kindness and compassion for weakness?

How can we start submitting to the idea that everything is interconnected and that the relationships between the parts dictate the outcomes more than the parts themselves?

What will it take to break out of the paradigm of the company as a machine to be optimized and into one of a living system to be nurtured and evolved?

Until next time, be well. 🙂

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed this post, please consider hitting the ❤️ button, subscribing for future issues on your inbox, and sharing it using the button below.

You can also follow me on LinkedIn where I share short thoughts on leadership and organizations daily.

Fantastic essay, Paulo! I really enjoyed reading about your thoughts and impressions of Dr. Deming and his life.

Thank you for the deeper lesson on Deming. I've always been a fan, and now I'm even more so.

Conscious capitalism (while not a great moniker,) is an area I've been researching. Trying to find a way to balance the benefits we get with an open market against the seemingly inevitable outcome of income inequality that results. It's an area for deeper thought and more importantly, more experimentation.