What if I told you I can give you a pill that will make you better at…

Handling conflict

Leading change

Gaining trust

Influencing others

Experiencing joy more than fear

…and that it has no side effects?

Would you take it?

What I’m going to share today is not exactly a pill (sorry). And some of my readers will probably already be familiar with it. But it’s as close as it gets to magic in making you a better leader. Like a cheat code, it makes you operate at a different level.

My coach training was with the Neuroleadership Institute, founded by David Rock, who wrote a number of excellent books on the intersection of neuroscience and leadership. All of them are highly recommended reading. Rock kind of coined the expression “leading with the brain in mind.”

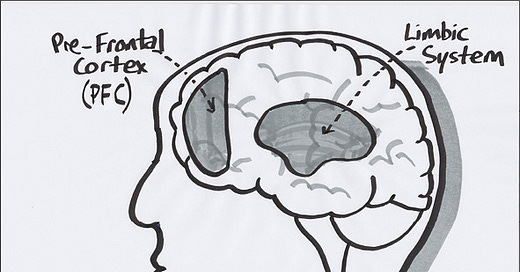

One of the simplest but most profound discoveries I made in my learning journey was that our pre-frontal cortex (part of our “thinking brain”) does not operate very well simultaneously with our limbic system (our “emotional brain”). It’s like a pendulum—the more engaged one is, the less the other can be.

Ever tried solving a complicated cognitive problem while anxious and stressed out about something else? Exactly.

The other crazy discovery is that social pain and physical pain produce similar brain responses.

Yet, because it feels very different, we act like that’s not the case. As Matt Lieberman put it in his book Social:

“We don’t expect someone with a broken leg to ‘ just get over it.’ And yet when it comes to the pain of social loss, this is a common response. We intuitively believe social and physical pain are radically different types of experiences, yet the way our brains treat them suggests that they are more similar than we imagine.”

Why does this matter? Because the workplace, to this day and by default, is full of social pain. Competition, hierarchies, expectations, pressure, uncertainty… the list goes on and on.

If our brain responds in a similar way to physical pain, is it any wonder that so many people often burn out? Unfortunately, our society teaches us from very early on that showing emotion is bad.

And so in silence many of us suffer. The negative impact on individuals, teams and, ultimately, business performance is enormous, insidious… and very hard to quantify. Out of sight, out of mind?

Changing this status quo is brutally difficult. The incentives at play all too often conspire to perpetuate these environments. Traumatized people traumatize people, while having the best of intentions all along—even when it doesn’t feel or look like it.

So, is there nothing that can be done about it?

Not quite so hopeless, I would say.

Enter SCARF

David Rock introduced the SCARF model back in 2008 in a fascinating paper where he points out that the “minimize danger and maximize reward” principle is an overarching, organizing principle of the brain. Furthermore, the model is supported by 3 key ideas:

The brain treats many social threats and rewards with the same or even greater intensity as physical threats and rewards.

The capacity to make decisions, solve problems, and collaborate with others is generally reduced by a threat response and increased under a reward response.

The threat response is more intense and more common, and often needs to be carefully minimised in social interactions.

Rock writes on the utility of the model:

“The SCARF model is an easy way to remember and act upon the social triggers that can generate both the approach and avoid responses. The goal of this model is to help minimize the easily activated threat responses, and maximize positive engaged states of mind during attempts to collaborate with and influence others.”

Think of your (and everyone else’s) brain at all times scanning the environment for threats or rewards across these five social domains:

Status. Do I feel less than or better than others? What is my relative sense of status?

Certainty. How well am I able to predict the outcomes of this situation?

Autonomy. To what extent do I feel a sense of control over my environment and my own choices?

Relatedness. Am I in or out of the group? To what extent do I feel like I belong or am I rejected?

Fairness. Is this a fair exchange or situation? Is my sense of justice threatened here?

As I learned about this model, I immediately recognized its usefulness. In my experience, it’s one of the models that most resonates with people because it puts into words what they’ve been feeling all along—the aha! moments are almost inevitable.

Along the way, I had a few realizations related to it:

The standard ways of working and organizing companies create threatening environments by default. For example, the pyramid-like hierarchical reporting structure explicitly threatens relative status—by design. This coupled with lots going on, many ambitious objectives, and pressure to deliver results incentivizes command and control approaches where employee’s sense of automony is often threatened.

Most people were never taught about this. Although in some niches the SCARF model is well known, by and large it remains unknown by the vast majority of leaders, managers and individual contributors. While this is exactly the type of stuff especially managers shoud be trained on, the focus on “hard skills” still reigns supreme (and so does anxiety and burnout).

If more people were educated on this, the impact would likely be tremendous. The beauty of this brain-based approach is that it can help mitigate a huge amount of threat in spite of the organization structures. In other words, a SCARF-savvy manager can make a direct report feel like a real peer (thereby reducing status thread), can try to provide more predictability (thereby increasing certainty reward) and can allow the person to do things their own way while providing effective coaching support so learning happens (thereby increasing autonomy reward).

Everyone has a different mix of SCARF domain sensitivity. For example, some of us feel fairness threats more acutely, while others are much more sensitive to being told what to do. Some are very sensitive to uncertainty—which probably makes working for an early stage startup a bad idea. This type of self-knowledge is helpful so you can better understand how your environment is impacting you. And you can also share it with your colleagues so they understand you better—and vice-versa.1

You can leverage some domains in the absence of others. A startup is an inherently uncertainty environment, often lacking structure and with no promise of success. There is not much you can do about that. But you can focus on other domains to compensate for it. For example, by increasing people’s sense of autonomy (provided they are aligned through quality shared context), their sense of fairness (by making your decision-making as transparent as possible) or their sense of relatedness (by investing in improving how people work together rather than have everyone working solo on different things.)

I could go on, but you get the gist. I don’t think I’ve ever come across a more important and useful model than this one. So here’s something for you to think about:

What are the biggest SCARF-related challenges in your work?

How can you leverage the SCARF principles to improve on them?

I’d love to read some of your ideas in the comments.

Before I go, I can’t help but share something I learned recently from Adam Grant’s latest book, Hidden Potential. In it, he describes the Finnish school system and the incredible outcomes it has generated over the last couple of decades. The details themselves are a story for a different day, but their biggest underlying assumption, which underpins their whole approach stuck with me:

“We can’t afford to waste a brain.”

Indeed. And we don’t have to. All it takes is will, and some skill.

The Neuroleadership Institute provides a simple, 5-minute SCARF assessment you can use for free.

![Chapter 7 The Science Bit: Leaders Do Not Know About the Power of the Brain - Leadership Insights [Book] Chapter 7 The Science Bit: Leaders Do Not Know About the Power of the Brain - Leadership Insights [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!rczC!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F34052d4e-a8af-48ac-98a6-d8af61e14af3_591x429.jpeg)

As a manager in a struggling startup, certainty and relatedness are my biggest challenges. When there are layoffs, people start to be concerned for their place. Sometimes their closest coworkers are gone, which adds to the temptation to leave. This increases the uncertainty for those who stay, creating a dangerous spiral.

I try to work hard on both points (didn’t name them as such until now). Providing financial certainty through talks with the CFO, and relatedness through more team events and activities.

It’s a tough challenge :)

Good read Paulo!