TWH#55: Human Battery Drain

How the systems we work in drain us, making self-care a critical priority, not a luxury.

Before we dive into this week’s post, I wanted to take a moment to express my appreciation to the Hagakure readers who engaged with me over Substack Chat last week. I got clear feedback that betting on shorter articles with an occasional longer deep-dive is the way to go. Thank you!

So, this week’s post is short(er) thanks to your input. The reality is that, as the saying goes, “If I had more time, I would have written a shorter letter.” Writing short and concise posts is harder than it seems. I’ll keep at it. 😉

Enjoy this week’s Hagakure and it would mean a lot to me if you liked and shared this post with others. ❤️

“It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society.”

— Jiddu Krishnamurti

They say that what gets measured gets managed.

They also say that not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.

There’s one critical thing that is really hard to measure, and it definitely counts. But because it’s hard to measure, it tends to not get managed. And, in many cases, that movie does not end well.

I’m talking about our energy. Human energy. Team energy. Organizational energy.

Unlike our smartphones, we don’t come prepackaged with a battery % indicator. Yet, we have one nonetheless. Some of us have a larger battery than others. Some of us spend our energy very quickly, regardless of our battery size, while others keep it super steady. And just like our smartphone battery, after a while it never truly goes back to 100%.

I have witnessed many people burn themselves out and believing it was their fault. That something was wrong with them.

I’m here this week to say there isn’t. And that, to lean on Krishnamurti’s quote for a bit, it is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick system of work.

Here are 3 examples that help illustrate why that is.

Constant Context Switching

Many of my clients are heads of engineering or product, and their calendars are hair-raising. A never-ending game of Tetris made worse by the insane amount of topics they have to care about. The amount of context switching is preposterous.

Meetings, however, are not the only offender. Tools like Slack and Teams are right up there, too. The explicit cost of using these, in both time and social capital, are so low that they are routinely used—and abused. After all, you no longer have to get off your butt and physically go interrupt a colleague.

The implicit costs, though, are less obvious. We are wired for social connection. To our brain, an inbox full of unread email, or having a bunch of Slack notifications waiting is the psychological equivalent of ignoring a tribe member.1 It's no wonder then that a 2018 report revealed that:

The average knowledge worker “checks in” with communication tools every 6 minutes.

40% of knowledge workers never get 30 minutes straight of focused time in a workday.

It’s either feeling anxious because you’re letting others down, or being constantly frazzled, whiplashing left and right, trying to keep up. And still being anxious because you feel you’re slowly but steadily losing ground.

To add insult to (literal) injury, a recent research study done at Microsoft highlights the nefarious effects of back-to-back meetings on the brain. It shows a marked difference between stress levels, as measured by beta wave activity in the brain, when participants were back-to-back versus when they took 10-min breaks in between, and meditated using Headspace.

The study reached three main conclusions:

Breaks between meetings allow the brain to “reset,” reducing a cumulative buildup of stress across meetings.

Back-to-back meetings can decrease your ability to focus and engage.

Transitioning between meetings can be a source of high stress.

It’s no one’s fault that technology evolved to a point where this tragic way of working against the brain just became the default. But it’s everyone’s responsibility to become aware of how it’s hurting. And it’s even more so senior leadership’s role to make sure actions are seriously taken to prevent massive individual and organizational drain.

A Near-Permanent State of Threat

We tend to seek pleasure and run away from pain. But our brains are programmed to be a lot more attuned to threats than rewards. The explanation is simple: avoiding threats keeps us alive. Seeking rewards doesn’t do much for survival.

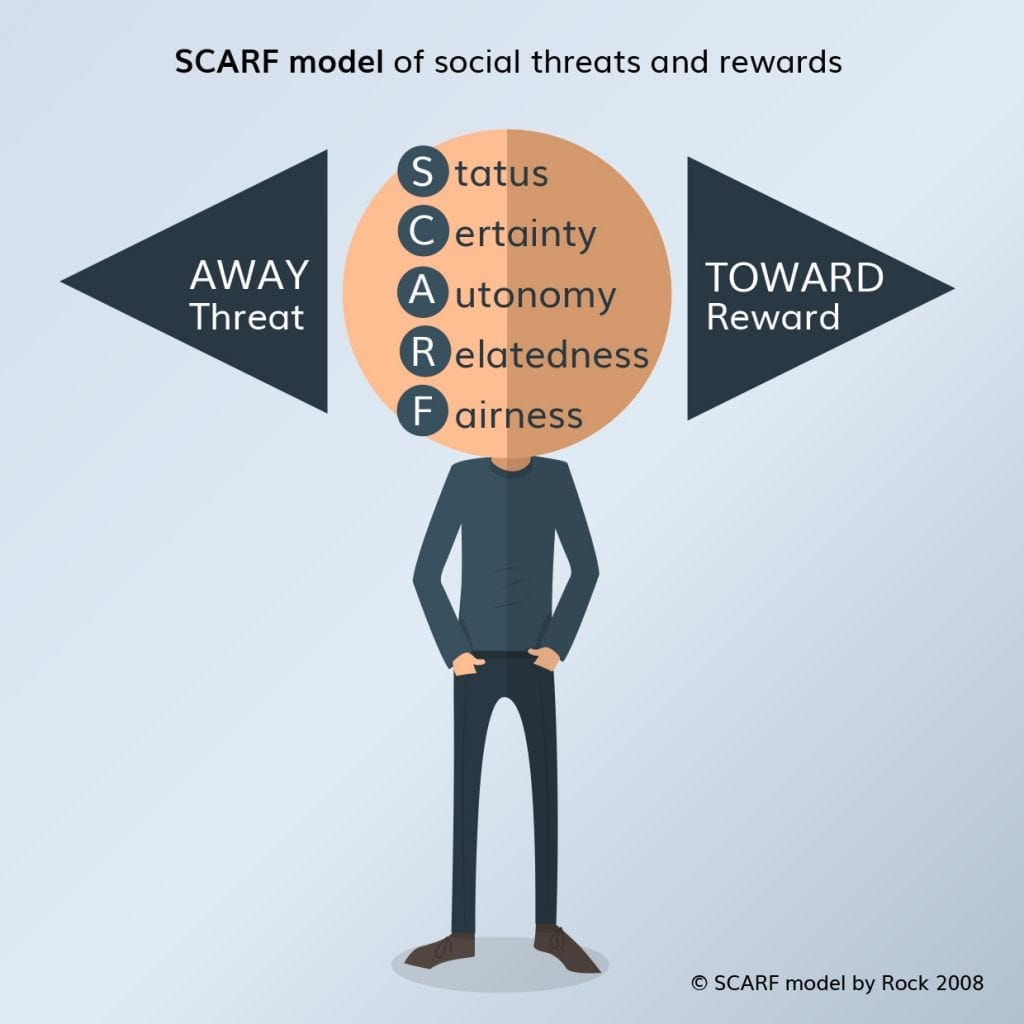

Although the workplace doesn’t threaten our survival per se, the reality is that our brains perceive threats acutely all the same, with all the attending physiological and psychological consequences. As I wrote about in a previous issue, David Rock famously devised the SCARF model, based on neuroscience research, highlighting what our threat/reward detection system scans for:

Status. Our relative importance to others.

Certainty. Our ability to predict the future.

Autonomy. Our sense of control over events.

Relatedness. How safe we feel with others.

Fairness. How fair we perceive the exchanges between people to be.

Now imagine:

A typical update-based 1-on-1 where the manager asks questions about where projects stand, when it will be delivered, what’s taking so long. Status threatened.

Strategy, direction, and priorities from above change all the time. Certainty and Autonomy threatened.

The sales team promised X to customer, pushes product development to build it but didn’t consult on feasibility before. Status, Autonomy, Fairness threatened.

Highly bureacratic promotion process that feels biased, and where the calibrations are not transparent. Fairness threatened.

I could go on and on. If this sounds familiar it’s because it is.

Threat states are not just a nuisance. They lead to the internal release of cortisol and adrenaline, inhibiting learning, creativity, rational thinking, and lack of emotional regulation. And, on a long enough timeline, burnout and leave. And we wonder why people don’t perform?

Introverts Not Welcome

20 years of experience in the industry make me strongly suspect that a decent majority of people working in tech are introverts. Disclaimer: I am a card-carrying member of the introvert club myself.

Introverts’ brains are different. They react different to external stimuli, being more sensitive and more easily overwhelmed by them. They have higher levels of prefrontal cortex activity, and their neurotransmitter mix also seems to be different.

Despite all this, companies default to being tailored for extroverts: emphasis on a lot of networking, open office layouts, and very rapid decision-making are just some of the typical traits. More pernicious is the typical career ladder which almost inevitably promotes publicly speaking up, being louder and more visible, thinking and emitting opinions on your feet. I have yet to see a career ladder that promotes good listening skills.

Another example are company offsites. Good intentions notwithstanding, the concept of “fun” seems to be extrovert-only. I was always terrified of them when I was an engineering manager myself. To me, the worst part was not even find ways to avoid the “fun”—I got pretty good at that. It was the sinking feeling that I was being regarded as weird, a party-pooper, not a team player, etc.

As Susan Cain, author of Quiet, says:

“We’re told that to be great is to be bold, to be happy is to be sociable. We see ourselves as a nation of extroverts – which means that we’ve lost sight of who we really are.”

If the majority of tech workers are indeed introverts, why is the workplace designed almost exclusively for extroverts?

So What?

All of the above are insidious, silent, and invisible energy drains.

When we’re constantly multitasking and switching context, the accumulated stress is invisible but it builds up over time.

When we’re in a state of threat, our hormones are duly preparing our body to fight, run away or, in many cases, freeze—in the form of resigning ourselves to fate, jaded and unhappy.

When we’re an introvert in an extrovert world, the mismatch is like a CPU stuck at 100% utilization, fans going full blast, battery draining fast.

The worst part? Our battery capacity goes down over time. Today’s 100% is last month’s 80%. Tomorrow’s 100% is today’s 98%.

This is a lose-lose situation. If we truly believe that businesses are nothing but the collective capacity, ability and talents of their people, we have to admit that we’re dropping the ball.

Or maybe we don’t really believe people matter that much?

And even if there’s some business “success”… what would it look like if our people were not operating at a mere fraction of their real potential?

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed this post, please consider hitting the ❤️ button, subscribing for future issues on your inbox, and sharing it using the button below.

Until next week, have a good one! 🙏

A 2015 study examined the effects on self, cognition, anxiety, and physiology when iPhone users are unable to answer their iPhone while performing cognitive tasks. All those outcomes were adversely affected.