TWH#54: Unshackling The Organization

There's a lot more to Netflix and "No Rules Rules" than hiring the best and getting out of their way.

Before we dive into this week’s post (a longer one, mind you, but I hope captivating nonetheless), I’m looking forward to interacting with some of the Hagakure’s readers through Substack’s new Notes feature.

I believe content creation online becomes a lot more meaningful by thinking and exchanging together. It takes humanity to bring the human back into the workplace.

The newsletter will continue to be a long-form place of exploration for better ways of working. I’ll be using Notes to share more of myself and my own personal journey, as a leadership coach, former engineering leader and, frankly, just someone who’s striving to be a better human.

You can also share notes of your own. I hope it becomes a space where every reader of The Weekly Hagakure can share thoughts, ideas, and interesting quotes from the things we're reading on Substack and beyond. 🙂

Back in September 2020, with the world still very much in the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic, a book with a solid red cover, its title in large, bold type was published:

I remember at the time that it seemed like every single CEO was reading this book, and gushing about it. It wasn’t surprising to me, considering the combination of:

A long history of business books claiming to have the recipe for greatness.

Netflix’s undeniable business sucess over the years.

Our attraction to the myth of the strong leader.

Our mimetic desire.

Our survivorship bias.

What was also not surprising? That the generalized key takeaway for most folks seemed to boil down to the trite, “Hire the best and get out of their way!”

We love simple explanations for complex phenomena. But in this week’s Hagakure, I explore why there’s a lot more to it than that. And how Netflix seems to have understood (and intelligently acted upon) a few key truths about working in complexity that the vast majority of other companies are blissfully—and painfully—unaware of.

Know Thyself

One thing that seems to hold true about any successful organization, be it in business, sports, community, or whatever else, is being very clear about who they are—and who they’re not.

Marc Randolph, Netflix’s co-founder back in 1997, writes in his wonderful book, That Will Never Work: The Birth of Netflix and the Amazing Life of an Idea:

So as a leader, the best way to ensure that everyone arrives at the campsite is to tell them where to go, not how to get there. Give them clear coordinates and let them figure it out. It’s the same at a startup. Real innovation comes not from top-down pronouncements and narrowly defined tasks. It comes from hiring innovators focused on the big picture who can orient themselves within a problem and solve it without having their hand held the whole time. We call it being loosely coupled but tightly aligned.

Loosely coupled but tightly aligned already hints at the fact that it’s not simply about hiring the best, turning them loose, sitting back and watching greatness unfold. It speaks to something that brings about both flexibility and some form of structure.1

Randolph goes on:

People want to be treated like adults. They want to have a mission they believe in, a problem to solve, and space to solve it. They want to be surrounded by other adults whose abilities they respect.

It’s that simple, and that hard.

No Rules Rules reads to me like the implementation manual for that particular quote by Randolph. Netflix knew itself intimately from early on, devising their north star as building a company that is able to adapt quickly as unforeseen circumstances arise and business conditions change. That’s the essence of being agile. Lowecaser ‘a’.

One criticism often leveled at these types of accounts is that of hindsight bias—that while they portray things as if they knew what they were doing all along, in practice they really didn’t. I do think that criticism has a kernel of truth to it. From a philosophical perspective, no one really knows what they’re doing when what you’re doing is attempting something completely new, in a highly volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous environment.

Where this criticism misses the mark is in failing to acknowledge that there are certain mindsets and approaches that make it a lot more likely to find better and better answers through discovery, learning, and iteration. From reading No Rules Rules, it became clear to me Netflix’s success is far from being “let’s throw stuff at the wall, and see what sticks,” or platitudes like “we only hire A+ players” (with often a terrible hiring process behind it.)

Instead, Netflix’s founders and early key employees (former Chief Talent Officer Patty McCord key among them) knew that they were not in the manufacturing business where you want to minimize variation and efficiently build a lot of the same widgets. They knew that creativity, innovation and adaptability were the name of their game which meant they wanted more variability, not less.

Complexity Conscious

Netflix understood that their company—like any other company—is nothing but a complex adaptive system, made up of many individual parts, with no one part effectively coordinating the action of others, and from which patterns emerge.

And that is where I believe the book title is nothing short of genius. No Rules Rules because in complex systems there are no rules as we have come to know them in the prevailing systems of management. Instead, one can only constrain the system in “soft” ways that attempt to influence outcomes, rather than control them.

Netflix’s way is just that—a way. But it hinges on a few general principles that I suspect underpin any thriving organization dealing in creative, knowledge work:

Create high levels of clarity, transparency, shared context, and trust.

Decentralize and increase quality of decision-making at all levels.

Continuous improvement, and a keen sense of developing competence.

Accept the discomfort of living on the edge of order & chaos.

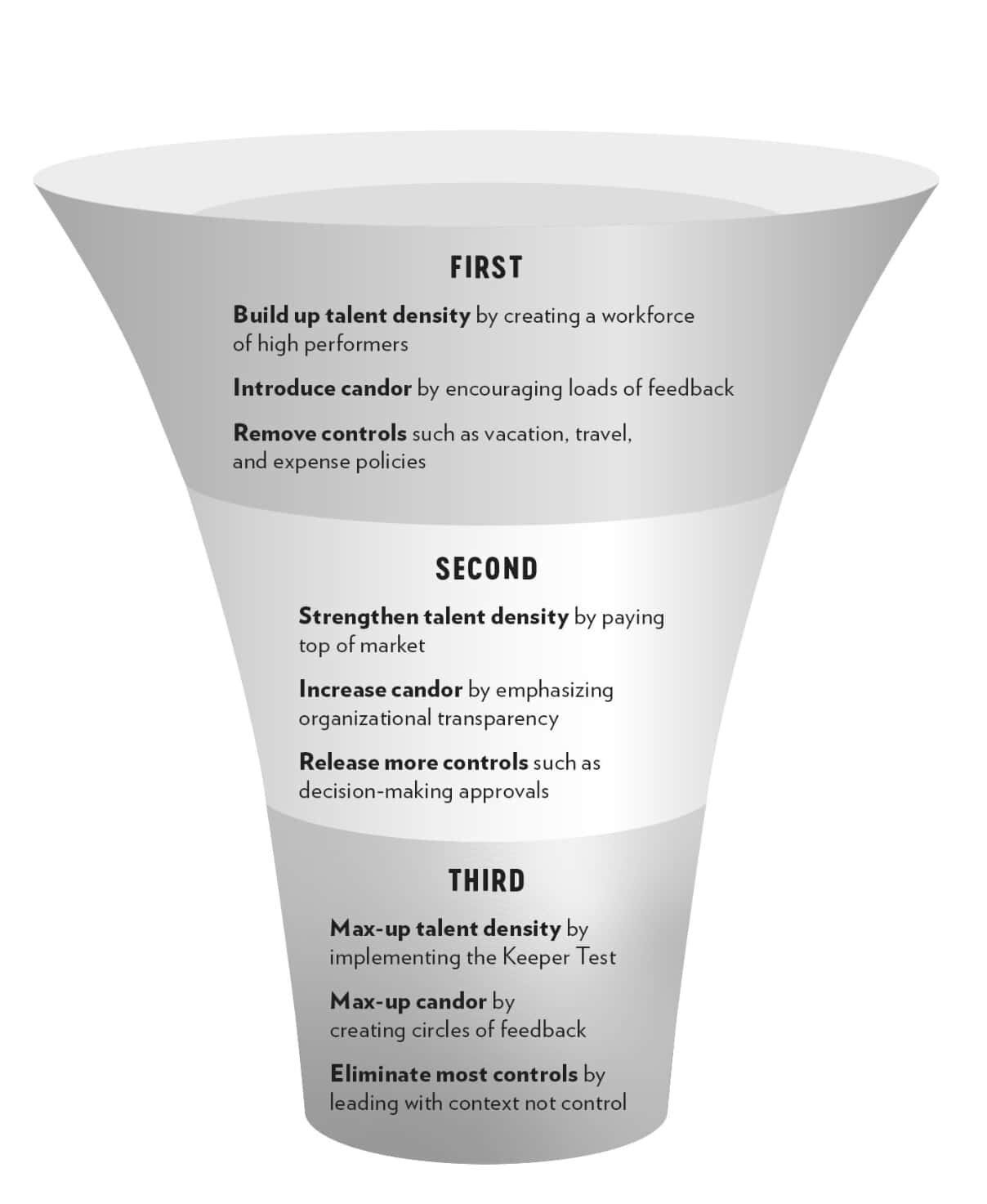

In Netflix’s case, they addressed all of the above at three fundamental levels: Talent, Candor, and (removal of) Controls. They did so over time in three interconnected stages, depicted in the book as a funnel of sorts:

Whereas almost all companies talk a good game of “hiring the best” and “radical candor,” the reality is that the majority simply doesn’t know where to start beyond the good intentions. And where it comes to controls, the fear and anxiety most leaders are gripped by won’t let them surrender to the idea that the more process and regulations they put in place, the more they work against themselves and their employees—ultimately increasing the levels of fear and anxiety in a never-ending death loop.

What follows is an exploration of some of the 3 fundamentals Netflix has put in place over the years in order to enact the complexity-conscious principles above.

Talent Density

Hiring the best (e.g. “getting the right people on the bus,” to use Jim Collins’ parlance) is certainly the bedrock on which everything stands. But that’s just the start.

Cutting across the entire Netflix approach is a ruthless focus on reducing any sort of drag. One such example that plagues most companies is compensation. How the organization tackles it is a good indicator of how it thinks about complexity and controls. Netflix makes a crucial distinction that is a non-obvious observation with significant downstream impact. Here’s co-founder, former CEO, and the book’s co-author Reed Hastings on the topic (emphasis is mine):

“We determinated that for any type of operational role, where there was a clear cap on how good the work could be, we would pay middle of market rate. But for all creative jobs we would pay one incredible employee at the top of her personal market, instead of using that same money to hire a dozen or more adequate performers. This would result in a lean workforce. We’d be relying on one tremendous person to do the work of many. But we’d pay tremendously.

This has profound implications.

For one, top talent started seeing Netflix as a company that pays top dollar for quality. These are typically people who are not scared by the prospect of working hard for something they are excited about. And one thing that definitely excites top talent is working alonside other top talent. This thereby created a self-reinforcing feedback loop.

Another implication is that mediocre-performing employees are a lot harder to deal with, and more time consuming. Note that this does not mean they are mediocre people or even mediocre professionals. It only speaks to their fit to this particular company, and its culture. With a lot less of these “misfits,” everyone else is freed to move forward in value-creating ways—including the ones that find a better fit elsewhere.

But the most profound implication might be the shift from paying-for-performance to paying top of the market, and adjusting periodically as needed. This actually severs the (always problematic) link between performance and compensation, whereby the incentive (often unconscious) becomes to please the boss, hit a metric, or whatever is perceived as linked to more status and more money. It’s also telling that Netflix seems to completely reject the idea of bonuses, seeing them at odds with their core principle of flexibility. Hastings again:

“I learned from that exchange with Leslie [Kilgore, CMO] that the entire bonus system is based on the premise that you can reliably predict the future, and that you can set an objective at any given moment that will continue to be important down the road. (…) the last thing we want is our employees being rewarded in December for attaining some goal fixed the previous January. The risk is that employees will focus on a target instead of spot what’s best for the company in the present moment.

There’s another perhaps less obvious observation: high performers will naturally want to succeed and will devote all resources towards doing so whether they have a bonus hanging in front of their nose or not.

So, instead of linking performance to pay, Netflix reinforced a different relationship: between performance and permanence at the company. And that’s where real candor comes in.

Maximum Candor

How many people working in companies have never at least heard of “radical candor?” But how many actually practice it?

I suspect the chasm between the two is immense.

The nebulous concept of candor, and how Netflix seems to have grasped it on another level in both theory and practice, is best illustrated with a story from the book itself. Larry Tanz, VP of Content who started at Netflix sometime in 2014 tells it:

For the past five years I’d been working for ex-Disney CEO Michael Eisner. Let’s just say those of us on Michael’s staff weren’t giving him a lot of direct negative feedback. Where I came from the boss might be candid with but any feedback in the reverse direction was pretty much unheard of.

In my second T-staff (Ted’s staff) meeting, Ted [Sarandos, Chief Content Officer and presently co-CEO] began by reminding the twelve of us that the written 360 was coming up in a few months, and that we all needed to be in the habit of giving frank feedback to one another. “Even if you don’t work together,” he said, “you need to be close enough to give candid criticism on an ongoing basis. We just finished a round of 360s with R-staff (Reed’s staff). I’ll just read to you the feedback I received.”

I was confused. What was Ted doing? In my entire life I’d never had a boss tell me what his peers and superiors were saying about him. My immediate thought was that he would cherry-pick what he told us and we’d hear a sanitized version. Then he proceeded line by line to read through the feedback from Reed, David Wells, Neil Hunt, Jonathan Friedland, and all those folks. He didn’t read many positive comments, although there must have been some. Instead he detailed all of his developmental comments including the following:

When you don’t respond to emails from my team, it feels hierarchical and discouraging, even though I know this is neither how you work nor how you think. Perhaps it is because we need to establish more trust, but I need you to be more generous with your time and insights, so my team can serve your organization better.

Your “old married couple” disagreements with Cindy are not the best role model of exec interchange. There should be more listening and understanding on both your parts.

Stop avoiding overt conflict within the team; it simply festers elsewhere and comes back bigger. The seeds of Janet’s flaming out and the drama of Robert’s role were planted well over a year ago. It would have been better to address both directly and head-on a year ago rather than have everyone suffer, and morale drop.

Ted read these items just like he was reading a list of food to buy at the supermarket. I thought, “Wow, could I be brave enough to share my feedback with my own staff?”

I decided to paste this long excerpt here because I feel it encapsulates a lot of what radical candor is truly about:

(Very) senior leadership is not just demanding results and asking where projects stand. Ted Sarandos is reminding people that “the written 360 is coming up” and that they’re all expected to be able to provide “candid criticism on an ongoing basis.” This is a strong signal of what’s important in the organization. But the written 360 is not a convoluted process that takes ages and ages to go through.

Leading by example. Sarandos doesn’t just set the expectation—he straight up shares the (tough) feedback he got from his own peers. This gets Larry’s juices flowing, who starts to ponder if and how he can follow this lead and do the same himself.

Feedback to the boss. Where most places advocate for feedback, it’s usually unidirectional (read: downwards) in practice. I once worked for a C-level who claimed there was no need to get feedback for himself because “he already knew what people would say.” At Netflix, feedback to the bosses is not simply encouraged, it seems to be expected.

True candor. The peer feedback Sarandos shared does not read as “beating around the bush”, “sugar coating” or the good ol’ “shit sandwich.” Instead, it’s atypically blunt, yet constructive and even kind. I have worked with another individual who had such a hard time delivering candid criticism that the receivers usually came away from the conversation feeling flattered rather than with something to really think about.

Why Netflix seems able to have this culture of candor starts with treating people like adults, and not institutionalizing a “performance review” culture2. While there’s a very clear expectation and agreement that written 360s are to take place (because candor is key), there’s no policy per se. Instead, there’s effective guidance on how to give (and receive!) effective feedback in the form of a “4A Feedback Guidelines” that literally fits in one single page.

From a complexity perspective, Netflix seems to have understood that the success of any organization (read: complex system) does not lie so much within the individuals as it does in the relationships between them. And candid feedback between people is what fortifies those relationships. Nothing signals respect and develops trust more than giving someone feedback—and then actually seeing them change based on it.

Remove Controls

Netflix’s whole philosophy about control seems to be well encapsulated in this quote by Reed Hastings:

I don’t want rules that prevent employees from making good decisions in a timely way.

This is where the guiding principle of “Freedom and Responsibility” stems from. The catch is that freedom and responsibility, while nice to talk about and hope for, are not possible without high levels of talent and candor.

It also hinges on leadership that is based on “context over control,” leading to an organization that is, as mentioned earlier, “tightly aligned, loosely coupled.” This is, again, respecting a core aspect of complex adaptive systems: without the flexibility of being loosely coupled, the system cannot adapt. In the presence of stress, a system without flexibility doesn’t bend or reconfigure itself—it breaks.

Shared context won’t create itself. It starts with thinking differently, of which the following self-reflecting from Hastings is a prime example:

When one of your people does something dumb don’t blame them. Instead ask yourself what context you failed to set. Are you articulate and inspiring enough in expressing your goals and strategy? Have you clearly explained all the assumptions and risks that will help your team to make good decisions? Are you and your employees highly aligned on vision and objectives?

One of the biggest pitfalls of scaling organizations is tackling their challenges at the individual level first—and only. Hastings’ quote above shows a different mentality, enabled both by a degree of humility and extreme ownership. But it also speaks of taking a systems view. If my employees do not have the context to do a great job, that’s not an employee problem, but a system problem first: how is the data, information, and knowledge flowing to them?

A typical pushback on this idea is that many people are simply poor performers, don’t care enough, and therefore can’t be trusted. Call me what you will but I led hundreds of people over the years and I find that to be very rarely the case. What I did observe, over and over, is that the environment where people existed—typically siloed, with high levels of stress and anxiety, unclear direction and absence of leaders-coaches—led to predictably mediocre outcomes. It’s like expecting people to run fast but slapping a strait-jacket on them first. You’ll be lucky if they can even stay upright.

Netflix solves for this individual trust and capability challenge at the root: by increasing talent density and improving it continuously through maximum candor. With high degrees of both, the tenets of leading with context don’t seem so crazy anymore3:

Don’t tell employees what to do.

Give them context to dream big.

Give them inspiration to think differently.

Give them space to make mistakes along the way.

Those are about enabling/accelerating folks on discovering, learning, and executing. But what about the hoops that employees so often have to jump through? Netflix calls the following hoops “ways of controlling people rather than inspiring them.”

Vacation Policies

Decision-Making Approvals

Expense Policies

Performance Improvement Plans

Approval Processes

Raise Pools

Key Performance Indicators

Management by Objectives

Travel Policies

Decision Making by Committee

Contract Sign-Offs

Salary Bands

Pay Grades

Pay-Per-Performance Bonuses

When you put it all together, it makes you wonder how anything of value to a customer ever gets done. Or, more pragmatically, how much more value we could be adding if we didn’t have to deal with all this stuff.

Netflix, apparently, doesn’t. And in No Rules Rules we learn the 3 simple company rules that enable an environment of trust necessary to remove most—if not all—of this crap:

Always act in the best interests of the company.

Never do anything that makes it harder for others to achieve their goals.

Do whatever you can do to achieve your own goals.

In that order.

Are you spending lavishly on meals and hotel rooms because you got the company credit card, no questions asked? Well, there is actually a question asked—are you acting in the best interests of the company?

Are you acting selfishly because you have all the autonomy and can do whatever you want? You’re probably making it harder for others. That’s a no-no.

Are you mindful of what’s best for the company and what others need (through a ton of shared context + trust)? Then you can go ahead and do whatever you need to achieve what you need to achieve.

In Closing

For every person who raves about how company X is awesome, there will be at least another claiming that “oh, that won’t work here.”

Unfortunately, as I wrote last week, it’s too easy for learned helplessness to set in:

I have seen many people being so jaded by their current circumstances that they start believing that “everywhere is like this, what’s the point anyway?” And that’s objectively not true. Yes, every place has challenges and problems to solve. But different places have different people. I always tell folks I mentor that a lot of their wellbeing depends more on who they choose to go on the journey with than what journey it happens to be. Because the right journey with the wrong people is still the wrong journey to go on.

The bottom line is this: learned helplessness is learned and can be unlearned.

Or as Aaron Dignan points out in Brave New Work, capping a phenomenal exploration of the history of how the current machine-like organization came to be:

Our way of working is completely made up. This isn’t the way it has to be, or even the way it always was. Our way of working was created, brick by brick, by gurus, industrialists, robber barons, unions, and universities—generations of managers and workers who came before us. We can thank them for what is still serving us, and we can change the rest.

The point I’m trying to make with this deep-dive is not that Netflix is perfect, amazing, phenomenal. It’s certainly not that everyone should do what Netflix does. And I’m pretty sure they have their own share of dysfunction, and mistakes made. Morever, if you try to copy Netflix—or any other company for that matter—you will likely fail.

I’m also mindful of the survivorship bias I mentioned in the beginning. For every successful company there’s many others lying six feet under who had similar approaches. Business success has too many variables you can’t control.

But as far as variables you can control, Netflix seems to have done a pretty good job over time. The point of this post is to illuminate how their practices seem to all stem from being complexity conscious and people positive. It’s not so much how they do things, but how the things they do play to the complexity, uncertainty, and variability of their line of work rather than blatantly against it.

It is my hope that this post inspires you to explore more, and to ponder how you can think differently about your own team and organization. I hope it gives you some of the courage necessary to challenge the status quo, with kindness and firmness.

Remember: our ways of working are entirely made up. They can be “unmade”… and “remade”.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed this post, please consider hitting the ❤️ button, subscribing for future issues on your inbox, and sharing it using the button below.

Until next week, have a good one! 🙏

This is a classic case of a polarity (flexibility::structure). I strongly encourage you to learn more about managing polarities, and this article is a great introduction to the topic.

Performance review and calibration processes in larger companies (and even in some smaller startups) are aberrations that suck out the time, the energy, and the life out of the very people who are also supposed to “deliver.” It’s literally insane how long and demanding these HR-instituted processes often become.

It reminds me of the beautiful quote by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.”

That's a terrific summary of the takeaways from the book! The takeaway: "if you try to copy Netflix—or any other company for that matter—you will likely fail." is a very good.

You can agree with the principals, and even adopt some of them (and I think the 'funnel' drawing is pricesless), but you have to adapt. Each company/culture/era is different, with unique circumctences.